Why Markets Always Beat Central Bankers and Presidents

by David Stockman via International Man

Goodness me, even the Wall Street Journal is catching on. In a piece about the inflationary rebound theory of a former UK central banker named Charles Goodhart, it actually tees-up the possibility of high inflation for a decade or longer due to an adverse, epochal shift in the global labor supply.

He argued that the low inflation since the 1990s wasn’t so much the result of astute central-bank policies, but rather the addition of hundreds of millions of inexpensive Chinese and Eastern European workers to the globalized economy, a demographic dividend that pushed down wages and the prices of products they exported to rich countries. Together with new female workers and the large baby-boomer generation, the labor force supplying advanced economies more than doubled between 1991 and 2018.

He got that right. Now, however, the working-age population has started shrinking for the first time since World War II in developed economies, compounded by an ever more generous banquet of Welfare State free stuff that is shrinking the available labor pool even further. At the same time, China’s working force is expected to contract by a staggering 20% over the next three decades.

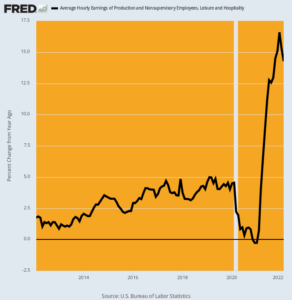

Needless to say, as global labor becomes more scarce, developed world workers will finally have bargaining leverage to push up their own previously stagnant wages. In the US leisure and hospitality sector, for instance, where worker shortages are most acute, Y/Y wage gains have averaged 15% for the last three months running.

And that’s not a “base effect”, either. On a two-year stacked basis, the gain from the February 2020 pre-Covid peak was 7.3% per annum. That’s nearly triple the average annual gain during much of the last decade.

Y/Y Change In Hourly Earnings of Leisure And Hospitality Workers, 2012-2022

But on the margin it is the draining of China’s rice paddies of subsistence labor that is fueling the now unfolding epochal change in the global labor cost curve and supply chains. As China’s workforce continues to shrink and fewer rural workers have moved to cities, its domestic labor costs have predictability risen.

U.S. manufacturing wages, in fact, are now less than four times as much as those in China, compared with more than 26 times when China joined the WTO in 2001, according to recent research by investment firm KKR. And that’s just the warm-up: China’s workforce is expected to shrink by about 100 million over the next 15 years—an economic pile-driver that will cause the deflationary “China Price” of the past three decades to morph into the inflationary “China Price” in the years ahead.

Moreover, this was all already well underway owing to the natural, baked-in demographics of the global labor market. But now that Washington has jumped the shark with its rabid Sanctions War against the global trading and payments system, the shift is likely to be sharply aggravated.

That is to say, the 26:1 labor cost advantage China possessed in the early 21st century when the supply chain was globalizing at break-neck speed was even then off-set in part by all the non-labor factors that go into global sourcing of goods. These include transportation costs, insurance costs, extended inventory pipelines, quality control, product delivery and availability risks, periodic premium costs for expedited shipping and much more. Yet on balance the former well outweighed the latter, causing delivered product prices to systematically fall.

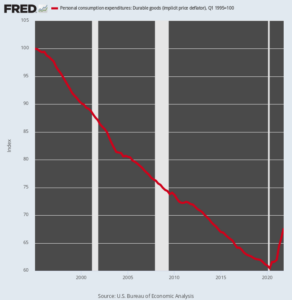

As we have frequently pointed out, the proof of the pudding is in the PCE deflator for durable goods, which got massively off-shored into the low-cost nooks and crannies of the global supply chain during the “inflation sabbatical” of 1995-2019. As it happened, the index dropped by a staggering 40% during that period—a one-time deflationary plunge that has no precedent in economic history.

PCE Deflator For Durable Goods, 1995-2022

Now, however, the potential upside of all these non-labor supply chain costs and risks have increased dramatically. In a word, global supply chains are going to get reeled-in and shortened dramatically because in many instances the labor differential will no longer profitably offset these associated costs.

Stated differently, the “lowflation” canard was always a statistical mirage, but under the double-whammy of rising global labor costs and soaring supply chain expense, there will now be no doubt. Substantial, persistent inflation in the cost of goods will become the order of the day, leaving the easy money central bankers of the world no choice except to finally shutdown their printing presses.

Needless to say, this will leave the permabulls of Wall Street in a world of hurt and for years to come. That’s because the corollary of the now ending Inflation Sabbatical of 1995-2019 was the massive off-shoring of America’s productive economy, tracked by the relentlessly plunging deficit on goods and services.

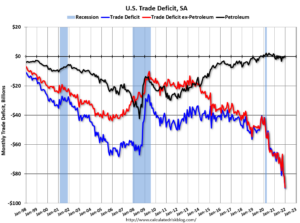

The recent release of the January 2022 trade balance leaves little to the imagination, recording a record deficit of $89.7 billion for that month alone. Moreover, this figure includes credit for the $19.2 billion surplus on services, meaning that the actual deficit in merchandise goods taken separately was nearly $109 billion. That’s an annualized run rate of $1.3 trillion!

Of course, when global goods prices climb steadily higher under the aforementioned double-whammy of rising labor costs and de-globalization of supply chains this massive exposure to imports will whoosh through the US economy like green grass through the proverbial goose. As it does, our clueless Keynesian central bankers will be proverbial too, as is in deer in the headlights.

That is to say, what we have is an economic boomerang. When the supply chain was going out to the cheapest corners of the global labor market, deflationary forces came flowing back. But the inverse is now happening: Supply chains are reeling back in toward the domestic cost structure, meaning that inflation will come ripping back, as well.

US Trade Deficit On Goods And Services, 1990-2022

Actually, however, the true picture is more dire than suggested by the chart above. That’s because the non-petroleum share of the trade deficit has ballooned even more egregiously during the last three decades than the overall figure.

As shown by the red line in the chart below, the ex-petroleum trade deficit was just $8 billion per month in 1998 and now stands at nearly $90 billion per month owing to the fact that the fracking revolution has reduced the petroleum deficit (black line) to zero. This means that the inflationary whirlwind bearing down on the merchandise goods accounts will be all the more virulent.

And while we are on the topic of energy trade and so-called energy independence, now might be as good a time as any to correct that shrill Fox News drumbeat that the Donald got America energy independent and then Sleepy Joe blew it in less than a year.

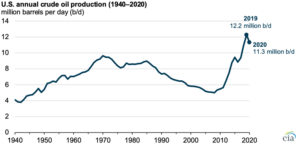

The fact is, presidents don’t determine the output level or the trade balance for any sector of the US economy—the forces of supply, demand and investment/disinvestment incentives do. The peak level of domestic crude oil production reached in February 2020 of 13.1 million barrels per day, therefore, was a consequence of the global petroleum price and investment cycle, not the Donald’s arm-waving, including the attempted revival of the Keystone Pipeline.

The latter was simply a cheaper way than rail to get Canadian tar sands to the refinery markets on the US gulf coast; it would have meant higher netbacks (prices received after transportation and other delivery costs) to Canadian oil sands producers, not more production or lower prices for American consumers.

Likewise, the Donald’s more sensible public lands leasing policies were clearly superior to those of Obama, but given the long lead-time between lease awards on public lands and actual new production, the impact was irrelevant in the time frame under discussion.

So what happened is what usually happens: The domestic petroleum production cycle had exactly nothing to do with four-year presidential terms. On that matter, the history is dispositive.

For example, during the freeze-in-your-cardigan-sweater term of Jimmy Carter, domestic oil production rose from 8.1 million barrel per day in January 1977 to 8.6 million b/d in January 1981, a gain of 5%. By contrast, during the 12-years of Reagan/Bush, where policy clearly was to dismantle Jimmy Carter’s price controls and unleash domestic production, oil output dropped steadily to 6.9 million barrels per day by January 1993, thereby marking a 18% decline in annual production.

Self-evidently what was at work was not the policy virtue or vice of the temporary Oval Office occupants during these periods, but the global petroleum cycle.

Likewise, during the pro-production term of Bush the Younger, domestic production declined from 5.9 million barrel per day in January 2001 to 5.2 million barrels per day during January 2009. By contrast, the opposite happened during Obama’s eight years, notwithstanding that the administrator was crawling with anti-fossil fuel types and environmentalist wackadoos.

Thus, by January 2017 domestic production averaged 8.9 million bbls/day, representing a gain of 70% from the level when ex-oilman Dubya left office. Again, however, this wasn’t presidential policy at work, but the global petroleum price, investment and production cycle.

And one obvious feature of that is the lag-time between when world oil prices peaked at $150 per barrel in July 2008 and the mobilization of investment and production technology in the US shale patch that brought domestic production roaring back.

Needless to say, that trend continued unabated during the Donald’s term, meaning that he was riding the inherited wave toward energy independence, not willing it into being through his Oval Office arm-waving and minor pro-production policy initiatives.

Accordingly, domestic crude oil production peaked at a historic high of 13.1 million bbls/day in February 2020, and then was monkey-hammered like rarely before under the combined impact of the worldwide crash of demand owing to the Covid Lockdowns and the fact that in the spring of 2020, the world oil price actually crashed to below $20 per barrel.

In the case of the US shale patch, that was an instantaneous death knell for new drilling. Yet owing to the deep and rapid decline rates of shale wells, lack of drilling translates into a plunge of production rates only a few quarters down the road.

So what Sean Hannity and the other Fox screamers don’t tell you is that by September 2020, domestic production had plunged to 10.7 million bbls/day or by a stunning 18%. That is to say, the retreat from energy independence happened on the Donald’s watch, long before Sleepy Joe ambled into the Oval Office.

In fact, by January 2021 production had remained plateaued at just above the September bottom at 10.9 million bbls/day. By January 2022, however, it had recovered to 11.5 million barrels per day, thereby digging out further from the hole dug at the end of the Donald’s term.

Again, that had nothing to do with Biden’s canceling the Keystone Pipeline (again!) or leases in the Arctic Wildlife Range. To the contrary, it was just the global petroleum cycle doing its thing, again.

Moreover, now that oil has again hit $130 per barrel and Washington’s madcap Sanctions War is likely to keep it there or higher, we can expect a new burst of drilling and production in the US shale patch. That prospect, in turn, has every probability of causing domestic crude production to top the Donald’s 13.1 million barrel per day record in the not too distant future.

So perhaps Sean Hannity and the GOP energy independence howlers should be careful of what they wish for.

US Crude Oil Production Ain’t Got Anything To Do With Presidential Terms

Reprinted with permission from International Man.